Table of Contents

- Introduction

About

Indigenous Futurism Model-Making Competition

Building the Lenape Center

Natural Resources + Government Policy

Mapping + Urbanism + Community

Virtual + Augmented Reality

ISAPD Chapter Kit

Interview: Regis Pecos of the Leadership Institute at Santa Fe Indian School

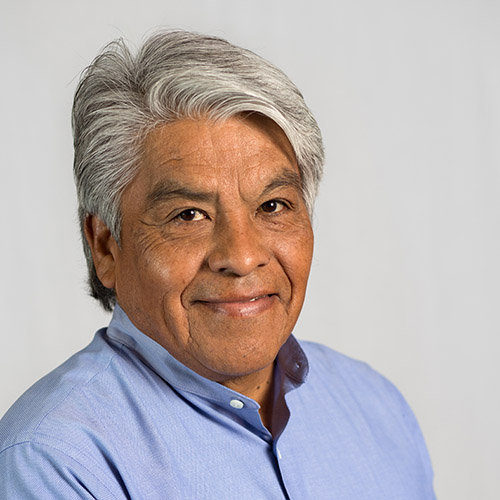

By Anjelica Gallegos, M.Arch.1 2021

As part of their Center for Architecture Lab residency, ISAPD conducted an interview with Regis Pecos, Co-Director, Leadership Institute at Santa Fe Indian School, focusing on issues of U.S. Indian policy and its impact on tribal architecture and lifeways.

Regis Pecos, a citizen of Cochiti Pueblo, has served as Governor, Lieutenant Governor, and as Tribal Councilmen of Cochiti Pueblo for over 30 years. Pecos made history as the first Native American trustee in the Ivy League when he was appointed a Princeton Trustee in 1997. For 16 years, he served as the Executive Director of the New Mexico Office of Indian Affairs. Pecos was the former Chief of Staff to the speaker of the New Mexico House of Representatives and former Director of Policy and Legislative Affairs for the Office of the Majority Floor Leader. Over 20 years ago, Pecos founded, and is currently the Co-Director of, the Leadership Institute at Santa Fe Indian School, a think tank for Native youth unique for its culturally-sensitive and community-based approaches that consider and transform the impacts of externally-developed policy on tribal community institutions.

U.S. Indian policy has historically changed and shifted tribes’ relationships to their natural environments, lifeways, and, ultimately, architecture. As a leader for Cochiti Pueblo and Indian Country for over 30 years, you know how to listen to your community and advance community needs and priorities through proposed or built projects. How is architecture related to co-founding the Santa Fe Indian School Leadership Institute?

With new opportunities created by the Indian Self Determination Act, the Community Block Grant Programs, Head Start Programs, Housing we have to consider the cumulative impacts over time. In the early days, all we did in our communities was replicate what we once criticized. One of the hallmarks of our Leadership Institute is examining the history and policies over generations and how they continue to impact our communities in unintended but in very consequential ways. In the construction of new facilities, these are permanent fixtures. In our Pueblo communities, our people were very conscious in the layout of our communities to be conducive to our social organization and conscious in creating the spirit of community. Our communities are constructed in ways that create a sense of mutual responsibility as an important core value. “It takes a village to raise a child” was coined long ago by our people before Hilary Clinton popularized it. It was and is a way of life.

When the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) extended housing opportunities to our members, we took it wholesale, not giving much thought to its destruction of the spirit of the community. In our worldview, community is a living spirit that we must nurture. Buildings have a living spirit. Prayer feathers are provided to keep the spirit to embrace the family’s wellbeing. It is given responsibility to be a place of peace and harmony, a safe place that should not be violated. When someone dies, it is why new sacred feathers are prepared, to put the spirit of the home back into a peaceful dwelling. When a home is no longer in use, it is why they are retired and blessed before being taken down in gratitude for taking care of generations of our families. It is, afterall, a living spirit. It is the ultimate expression of respect.

With HUD homes, it took the individual and cultural responsibility away from us. Someone else designed our homes. Someone else determined where homes should go. Building as many homes dictated their design and size. It was driven by what was cost effective. In our Leadership Institute, we ask questions of our fellows to help define issues to analyze. One of those questions is, “What do you love most about where you live and where you call home?” And we follow up with another question: “What threatens what you love most?” In an answer to this question, a young high school student responded and shared that living in the village and waking up in grandma’s house and enjoying the aroma of her cooking and the senses that come from a fireplace were special. Observing people meeting the sun and offering prayers. Watching the place come alive defined the aspects of community that define who we are, how we think, what we value, our relationships, our reciprocity. What could threaten a beautiful sense of the spirit of community? Her response was “Housing.” How? She shared that new subdivisions threatened and became the source of breaking up communities. The impact of subdivisions is very intrusive. They isolate the elders and children that are not mobile. They separate families. The architecture, cookie-cutter approach destroys the aesthetics and spirit and connections in multiple ways unimagined. You can never undo this. You drive from New Mexico into Arizona and across the plains and you see the same architecture. Makes no sense. What we did to embrace housing without much thought is to look at how HUD homes impacted the psychology of our people. All of sudden, it was an embarrassment to live in grandma and grandpa’s house because it was old fashioned, except for the millionaires who would pay huge amounts to live in a 100-year-old adobe home. It brought significant change. It brought a sense of disconnect.

Community block grants brought new opportunities to construct critically important community buildings: community centers, tribal offices, and, in some places, even kivas. The impact of this convenience added another destructive element. These community buildings were often built by the entire community. It was a collective effort. It had deep spiritual and community spirit attached to this. It defined what is called “community service,” “community work”. It literally belonged to everyone. It was built with the hands of the elders and the youngest doing their part. These buildings were annually refurbished as a community. Using commercial plaster that was popularized and became convenient destroyed the literal relationships with our hands to these dwellings. The hands of the people plastering these walls was an annual renewal of people and places of connection. The hands were literally imprinted on the walls of these community buildings. It was the nurturing hands of grandma rubbing and caressing your hands or your head. On one such occasion, as we were chipping away old plaster, we saw the hands imprinted in the wall. At that time, an elder called everyone to witness my discovery. The elder used this to share that, over generations, this annual ritual was just that: a ritual. It was renewing the relationship of place, of space, with us. That hand print could have been my mom’s, my grandma’s. It was the imprint of an expression of love to labor to make it strong so that the ceremonies, and when spiritual beings came to visit us, they could be welcomed into this space that we all labored to create and renew our relationships with annually. When commercial plaster became convenient, it displaced centuries-old practices. My grandpa said, “There will no longer be the handprints,” that were the evidence of our mutual commitment in the maintenance of the spiritual relationship of place and being. It brought to light how everything is purposeful and intentional. It is what gives birth to these physical places that have a purpose in creating an environment to embrace the people.

What becomes important in this discussion is to be mindful of the cumulative impacts of these impositions; that over time when we are not cognizant of simply replicating models, how it takes us away from the conscious connections of space and places and moves us into artificial spaces and places that have no life. They are hollow and spiritless.

What is an architectural project that stands out the most to you? How have cultural values been taken into consideration in the design and do you think it was effective?

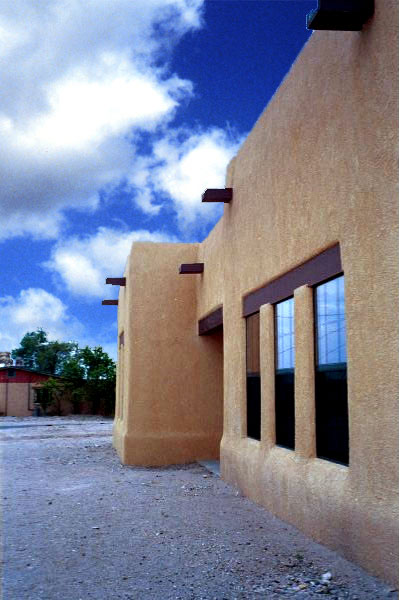

To answer your question, what comes closest to a conscious effort in creating space and a place consistent with the context I shared—it has to be the Cochiti Pueblo Senior Center [by Suina Design + Architecture]. What I learned was how we many times turn over the architectural design to someone who has no lived experience in our communities. What gets designed and built sticks out like a sore thumb—out of place. It is like a Space Age building next door to a kiva reflecting separate worlds. At the time, I was especially sensitive to the elders of a different time. New buildings were intimidating to them. It gave many a sense that they didn’t belong, living all their lives in an adobe home, simple but rich in its history of relations of family and community. Creating a place for them to gather that is artificial is just that—no life, unwelcoming, cold. I would equate it to being in a hospital; there is never comfort there.

We engaged in a process that asked them what would be especially “special” about a place for them. It was important what the external appearance looked like. Was it a building that would make them comfortable to walk into? It was important that it had the essentials of a home. It had to have a fireplace. The entrance had to be welcoming. It should have a living room to gather. Where they ate should not look like a cafeteria, but a home with long tables to eat together. It should literally be a home. There should be a place for storytelling by the elders when children come to visit.

It also had a place where elders could lay down and rest. It was designed where elders could stay engaged to make pottery or sew and men continue to make crafts or have private discussions. It was designed with a noninvasive clinic. It was designed as a day care for the more fragile, to keep as many home and not institutionalized. It was a place where families could bring their aging members and feel that their elder members were socializing and maintaining important ties to the people they have known a lifetime. This was the first elder facility designed with this deeper, conscious engagement for all the reasons I shared above.

Today, how have policy and past decisions affected people and architectures on tribal lands? Are architectures on tribal lands starting to incorporate cultural beliefs?

If we visit any community, we see the mess we have created that we cannot undo. These are tough lessons that have a destructive force. It represents a time when we did not ask the right questions. It was, in large part, the result of a long conditioning process that someone else knew better. It was part of an effort to modernize our communities. It was another way to assimilate us. It came from a deeper sense of self-hate of where we came from. It has taken several generations to reassess what those decisions of replication did to us. We did the same in education.

The first efforts to take over schools had a similar fate. In order to prove to our own people that we were capable of taking over education, the first thing we did was to replicate a public school model which we criticized as failing our children. But this was the best way we knew how to prove ourselves. Our brown faces replaced the white faces, but we did what we were critical of previously. We ask this question in our process: “What are we doing differently in this time of self determination, different from those times when others were in control and we were critical of?”

Head Start is a classic example; we totally embraced the program. Our Councils approved of them. Our people became teachers. It was no fault of their own. What we failed to ask was, “Where is Head Start a head start to?” To become fluent in English—at what expense? Our language. How was this different from the times when federal agents came to take the children? It was built on a mantra that the way you kill language and culture is to remove the children from their language and culture, and deny them their language and culture. Now we were implementing what we once criticized. Again, what are the cumulative impacts of this with housing, education, generally, and community building without our own vision?

Education that was not defined for us is at the root of this disruption. It is what compelled us to create the Leadership Institute. It is why we created the Summer Policy Academy for high school students. We teach the history of policies and laws and how they impact every aspect of our lives, our families, our communities, our governance systems, our way of life. It is built on defining our core values—hat core values define who we are, that define what we do, why we do what we do—and ask to share who gifted us those core values. Acknowledging who gifted us those core values to guide us in all that we do in our lives is the deepest expression of their love. How we live by them is how we honor them. It is what we use as our barometer and our guide to decision making, a paradigm that is conscious of the past, the impositions causing the intentional destruction and dismantling of our own systems and structures that sustain our worldview, our values, our culture, and our traditions. It makes us conscious of the present challenges and how they are deeply rooted in the past. How we respond to these present-day challenges defines what future generations will inherit from, just as what we inherited is defined by the sacrifices of all those who have gone before us.

In the future, do you think there is room for architecture in policy innovation to elevate cultural identities and secure the environment? Do you think preserving traditional architectural practices can ensure the continuation of traditional bodies of knowledge, like language?

In many cases, this discussion is at the heart of what we need to continue to provide. Creating new spaces and places for shared learning—for the examination and analysis across the spectrum to assess, evaluate how we got to where we are. What must we do to disrupt these impositions, to push back and reclaim our conscious thinking? If we fail, it only takes a couple of generations—your children and your grandchildren. If we do not intentionally transform our cultural knowledge in new ways, what we are discussing will not be in the realm of their thinking. That will be the ultimate severing of our relations to every generation we are tied to. We will break that connection that we have retained, that we have consciously maintained in conscious ways since what our elders teach us, since time immemorial.

That is why I am so grateful for your thinking and vision. We have to strengthen these relationships in very intentional ways. You are part of the answer to the prayers of our elders, that someday we would be blessed with people like you. It did not happen by design, and that is a reflection of why we do what we do intentionally in our Leadership Institute. To not be intentional is to run the risk of losing brilliant minds like you forever to something and somewhere else. It is what we cannot afford to risk. Thus, the intentionality of the things we do in our Leadership Institute. In 24 years of our work, we have conducted over 100 community institutes and over 3,000 Pueblo people and others have gone through our process to create a critical mass and a critical nucleus and community. If we asked ourselves how we end up where we are, there was no intentionality, There was no vision. But we were guided by the precious words of family and relations encouraging us along the way. And now by the grace of their continuing prayers, we are engaged in this discussion. I am grateful to you Anjelica. It’s a deep emotion of gratitude!

What is one fond memory you have with architecture?

The fondest memory I have with architecture is making adobes as a child for five cents an adobe. When I made hundreds and hundreds, I thought of retiring. [Laughs out loud.] At a critical point, my grandpa gave me cornmeal and asked permission from my dad to use me to build a home for my aunties. My grandpa used this word: architect. I didn’t know what it meant. He said we were going to build a home and I was going to be an architect. Where he learned that, I don’t know. He didn’t speak good English! But I became an architect very proudly. He would tell people that we were architects and people referred to us as that. I think it was his way of encouraging me. I was proud! We built one of the only remaining adobe homes still occupied today in Cochiti.

What is an Indigenous Futurism you wish to come true?

What I wish and pray about for our Indigenous Futurism is the return to a conscious re-engagement with spaces we create—places that have life to embrace us, to nurture us, to contribute to a sense of peace and comfort of these spaces and places we give birth to that reconnects us to conscious living. It is like a child in a mother’s womb. The environment we create must be the umbilical cord that shares the gift of life. Architecture is the creation of the spaces and places that nurture who we are, therefore the conscious creation of spaces and places is the assurance that what we cherish in our lives will be perpetuated by the spaces and places we create. Each part of what we create either enhances or takes away from how the environment we create nurtures all aspects of who we are. It is what defines us. So yes, it is at the heart of self expression of who we are.